Behind the research series, episode 1.

Funded by Horizon 2020, RECEIPT develops climate risk storylines that reveal how Europe is shaped by global climate impacts across five key socioeconomic sectors. In this interview, project coordinator Bart van den Hurk of Deltares explains how these storylines can meet a vital information need as the EU responds to climate change – and how questions of systemic risk are being brought into ever sharper focus in times of COVID-19.

RECEIPT sets out to explore the ways that climate change effects in other parts of the world can impact Europe’s economy and society. This sounds like an enormous task – how does the project approach it?

Traditionally, a scientist would tackle a topic like this by starting from the top and working their way down: using climate models beginning at the global scale, then zooming in on regional impact before narrowing down specific socioeconomic connections. But when the question is “how can global climate change affect Europe”, it’s true that the possible answers are so wide-ranging and complex, you need some guidance.

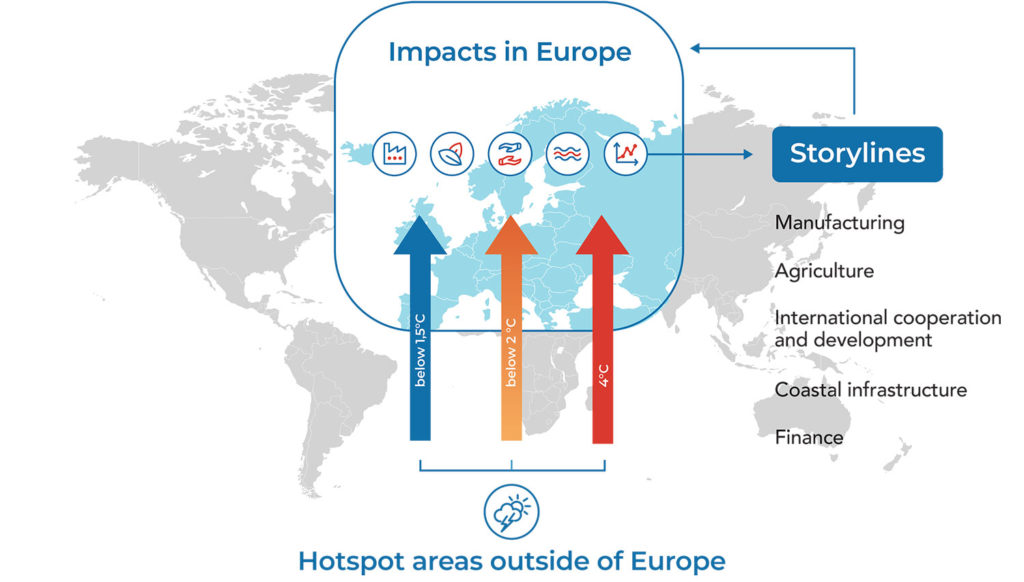

RECEIPT seeks to provide that guidance by adding a bottom-up approach, looking at how remote climate effects unfold in five sectors: agriculture, finance, international development, manufacturing and coastal infrastructure. The impact of climate change will be felt by stakeholders in these sectors in different ways, and outcomes can vary depending on how the future climate might look – whether the world is 1.5 degrees or 2 degrees warmer than today, for example, or whether we’re facing a world with enhanced regional rivalry or more international cooperation.

What is the added value of taking a sector-specific view?

For over ten years we have been aware of a ‘climate information gap’ that exists between the big-picture data provided by modelling institutes, and the specific information needs at the sectoral level. These needs can vary greatly, even within a single company. Take a hydropower plant: the infrastructure management team needs data to plan years ahead, while the reservoir management team might need information month-to-month, and those responsible for electricity production work with even shorter time frames. They all rely on climate information, but tailored to their specific role. And they have perhaps just 5% of their time available to devote to the topic.

This means we need a way of providing information that is practicable and accessible. In RECEIPT, we do this by way of ‘storylines’: detailed, internally consistent and plausible chains of cause and effect that reveal how Europe is vulnerable to climate change in other parts of the world. By condensing the immense range of future possibilities out there, we can manage this uncertainty for the users of climate information.

How did the storyline concept come about, and how are you building this approach through the project?

Like myself, a number of researchers in the RECEIPT team are active as lead authors of the IPCC reports – so we are very aware of the need to explain climate information in a way that is accessible to society more broadly. This was the motivation behind the storyline idea. The project develops it further by bringing thinkers on storyline development and underlying scientific methodologies together with experts on sectoral climate impacts. In addition, the RECEIPT team includes societal partners who bring to the table complementary insights from their work in specific sectors. This collaboration builds a transdisciplinary approach to the research, helping bridge the worlds between science and society.

How do insights ‘from the ground’ in the various sectors feed into the research?

One way is through identifying ‘micro stories’ that complement the central storylines and feed the imagination of individual stakeholders. For example, if a storyline depicts how climate change in Asia impacts the clothing industry in Europe, we can enrich this with a story of one specific clothing manufacturer in Poland, who may be facing disruptions in supply if drought affects cotton production, while at the same time being sensitive to a shock in demand if consumers want more eco-friendly garments. This story distils the bigger context down to a dilemma that an individual manufacturer can readily recognise and relate to.

RECEIPT will also show how climate storylines would play out in a future world that is 1.5 or 2 degrees warmer than today. Do you think that bringing these more extreme projections to life can make clear the urgency of taking action now?

I think there are two things to keep in mind. First, we will need to see a path taking us from here to there: if we have a scenario that is cast in the far future but not connected to the decisions we need to take today – that is difficult to engage with. Secondly, if we have a scenario that is only doom and gloom, it will either be rejected because it’s far away or improbable, or it paralyses people because they think ‘well there’s nothing we can do anyway’. This is why scenarios should always include adaptation options – there has to be some hope or some perspective that emerges from them.

An important outcome of RECEIPT will be to highlight the nature and impact of systemic risks – how a shock in one arena can ripple throughout our economy or society. Of course, the current COVID pandemic is confronting us with a systemic shock unlike many of us have experienced before. Do you think this can create a better appreciation of the systemic nature of climate risk?

There are certainly parallels between the COVID crisis and climate change: both are global in nature and both rely on remote teleconnections. But it is hard to imagine a climate shock with the same simultaneous globalised nature as COVID. Climate shocks will happen much more gradually, and though many of us will face extreme weather events as a result, these will not necessarily occur at the same moment. It’s a like a slow-motion version of corona. So we will need to highlight the important differences in how these crises unfold, and realise that lessons learned from coronavirus adaptation will not all be transferable to climate policies. We will still need specific approaches for climate.

What is the biggest impact you hope to achieve through RECEIPT?

In terms of scientifically formulated ‘outcome expectations’, I expect that at the sectoral level and the systemic level we will be able to provide new insights on options for where resilience to climate extremes makes most sense – showing how different resilience policies can lead to different outcomes under one scenario or another.

On a personal note, I would like if the storylines we produce inspire people to engage with the bigger story we are telling: that this planet is cracking under human pressure, and we need to reconsider our practices to avoid collapse. It might seem a bit Euro-centric to investigate how climate change in other parts of the world ultimately affects European industry or agriculture. But this can actually raise awareness of the fact that we are all in the same game, living on the same planet and reliant on each other’s wellbeing. If we can tell stories that illustrate that interconnectivity and shape a mindset of improving resilience not only for Europe but the world as a whole, that would be a very positive outcome indeed.

Bart van den Hurk is an expert in the field of weather and climate information at Deltares, an institute for applied research in the field of water and subsurface, based in the Dutch city of Delft. He has specialised over the course of his career in climate change scenarios, land-atmosphere interaction, and weather and climate modelling. He is Professor in the field of Interaction between Climate and the Socio-ecological system at VU University Amsterdam, and Lead Author of the 6th Assessment Report of IPCC.

Published on : 21 June 2020